Just a quick and tiny acrylic sketch, 2.5″ wide, in a wee frame. Image is from the episode The Adventure of the Cheap Flat.

Month: January 2016

The London Syndicate, Chapter 2

*** For newcomers: the best place to start is the preface/explanation, and Chapter 1, which can be read here. ***

Chapter 2: The Rival Gang

It was an ordinary Wednesday evening in August. I had spent the day visiting friends several blocks away from the flat which Poirot and I shared, and had been taking advantage of the hazy, comfortable summer evenings for lengthy strolls about the neighbourhood. The hour was late, and the sun had long since set. Stars were appearing in the darkening sky, and as I rounded the corner of the second block of my familiar route, my eye was drawn to the somewhat dilapidated warehouse that stood a little ways back from the street. It was, as usual, a lonely, forbidding-looking place; but something out of the ordinary struck me. Peering across the street into the gloom, my eyes fastened on a few narrow beams of light from electric torches. A small band of people were standing just outside the building in the side lane, and– were my ears deceiving me?– a funny, muffled sound. It suggested something like a cry for help, but I could not be sure.

Without hesitation, I strode across the lamp-lit street and made my way toward the mysterious figures. The shadows closed in again as I approached. But before I could say a word, I felt a sharp shove from behind. Stumbling and exclaiming in surprise, I looked up to see the figures coming up quickly. A heavy hand clamped onto my shoulder, preventing me from rising. When the figures came into full view, my blood froze.

I had heard of Mauta before– heard of the gang’s ties to a certain Indian family, their occasional clashes and animosities with the larger and better-organized London Syndicate, their distinctive scarlet insignia. But as the swarthy faces of four ruthless-looking men, dark scarves on their heads, glared down at me, one particular detail about the gang swam before my mind: unlike the Syndicate, they had no compunctions about murder. Also unlike the larger gang, Mauta was, as far as anyone knew, a very small and comparatively inactive band. But the incidences that had been connected with their name– mostly related to drug-smuggling– had also involved vicious incidences of murder. I’d no idea that they had operations anywhere near this neighbourhood.

Struggling against the pressure on my shoulder, I managed to get to my feet, casting a quick glance around for a possible source of that muffled cry I’d heard. But I saw no one else at all in that shadowy lane.

‘Look here–’ I said, as steadily as I could manage, but the tallest of the four shadowy men cut off my feeble protestation.

‘I know who you are,’ he said, a slightly eastern inflection in his growling voice. He shone his torch in my face. ‘You work with the detective Poirot. He is a busybody. Mauta has engagements that will not be interrupted by any interfering investigator. You tell him that.’ I forced myself to squint through the blazing light into the dark, shadowed face. His eyes were hard and black. The men on either side of me closed in. The scarlet insignia of Mauta winked out of the darkness from their scarves. In spite of the danger, their insolence galled me, and I found myself speaking.

‘Poirot doesn’t respond kindly to threats, especially from the likes of you.’

The initial blow came so swiftly that I have no recollection of feeling. There was a dizzying moment of blackness; then as the light swam back into view, so did the realization of pain. Several blows followed, then stopped suddenly. The man who had been speaking to me had presumably stayed the attack. He stooped down to where I was sprawled on the ground.

‘Do you know what we could do to that little Belgian?’ he hissed softly. ‘He would not last five minutes.’ I started and tried to raise myself up on my hands, but my limbs were like lead. The man’s tone was caustic. ‘Perhaps you think your friend is too smart for us. But there is such a thing as being caught unawares. And for those caught by Mauta… there is no escape.’

* * * * *

My head was spinning, and the torch light seemed to grow dimmer. When I felt myself fully coming to once more and could sit up, I realized that it had indeed grown dimmer; the men had retreated and vanished, leaving me alone in the dark lane. I paused and took a few deep breaths. The action of my lungs was sore inside my chest, which had been struck several times. I rose shakily to my feet, my heart pounding, and found that I could walk. As quickly as I could manage, I strode back across the street and back to my regular route home. The thought had taken hold that I must get back to the flat and find Poirot. My regular action of passing that warehouse on my walks must have spooked the gang called Mauta, and they thought Poirot and I knew something of their movements. Was that location used for their drug smuggling? Of one thing, I was certain: Poirot was not currently on a case involving Mauta, nor smuggling of any kind. He had been tracking certain movements of the London Syndicate, a gang that could only be considered a rival of Mauta. In a way, my encounter had been fortuitous. In their determination not to have Poirot on their track, they had actually given themselves away. Some crime was certainly imminent.

I paused, worried. The gang had told me to pass along their warning. Poirot himself would want me to tell him what had happened that night. But if I did? Surely he would throw himself into the case. He was so confoundedly sure of himself, but what he was up against! I knew that my friend was no coward. He had worked undercover against the Bosch in Belgium and France and had taken a bullet. In the police force, he had shot a man once who was on a murderous rampage. But nowadays, I had a difficult time reconciling that past character with my eccentric, elegantly-dressed little friend, for whom dust and tight patent leather shoes were about the most galling physical misfortunes he was likely to encounter. The dark man was right: brilliant as he undoubtably was, Poirot would not last five minutes if taken unaware by a force like Mauta. I’d had a lucky escape myself.

Feeling weary with bruises and mental exhaustion, I looked up to suddenly find myself at our block of flats. I’d reached my decision: Poirot must not be told about the events of this evening. Going after the London Syndicate was one thing, but Mauta… no, that was against all reason and common sense. I ascended to our floor and quietly unlocked the door of the flat. As I entered, Poirot’s voice rang out at once from the sitting room.

‘Hastings, my friend, you arrive! Somewhat later than usual, n’est-ce pas?’

Avoiding his line of sight, I replied something about my extended visit with friends, and fancying a bath before bed. Then I divested myself of my jacket and slipped quickly into the bathroom. Yes, I looked a dishevelled mess, all right. Insofar as anyone could hide evidence from Poirot, such was my goal. I drew the bath and spent the next twenty minutes scrubbing away all traces of grime and trying to relax my aching body, which was indeed sporting a number of dark purple discolourations. By the time I was in my pajamas and dressing gown, I judged it safe to make an appearance.

Poirot, immaculate in a rather garish dressing gown of his own, was settled serenely in a very square armchair, reading a letter. The empty cup that had held his evening hot chocolate sat on the nearby table. He looked up quickly as I entered and removed his pince-nez. I thought of the cold, dark eyes of the Indian gang leader and how different they were from Poirot’s warm, frank ones. Then I imagined what my friend might look like now if he’d been with me on my evening walk. Unable to hide a wince, I saw the small frown gathering between Poirot’s eyes in return. He had, in the past, entertained some truly ridiculous notions about what he called my ‘speaking countenance,’ but on this occasion, I realized that I had in fact let my guard down for a moment. I hastened to rearrange my features.

‘Lovely night for a stroll,’ I said in what I hoped was a light, airy voice. ‘Good visit with old Hodgkins. You’re up rather late yourself, aren’t you?’

Rising to his feet, Poirot tucked away the pince-nez and smiled. ‘I was hoping for an audience with your good self.’ He tapped the letter in his hand. ‘Japp has sent some communications about our friends the London Syndicate.’

I was suddenly struck by how very small he looked. His overweening self-confidence (not to mention his impressive and luxuriant moustaches) often managed to disguise the fact.

‘Look here, Poirot,’ I said with a sigh. ‘The odd murder case or jewel robbery are one thing. Organized crime on a large scale is rather another, don’t you think?’

My friend’s eyebrows rose. ‘Is this my friend Hastings who speaks? Who was so eager and willing to go after the Big Four? Mon Dieu, but I do not believe it!’

Irritably, I threw myself into the other armchair and said, ‘I’d rather you not get mixed up in anything of that sort again, thank you. I don’t fancy reliving your funeral.’

‘Ah, that troubles you, my friend? You have the good heart. But this organization is a local one, and though they are cunning, they are not eager to kill like the Big Four.’

‘I know you’ve been keen on this London Syndicate outfit lately, but I daresay there’s worse out there who wouldn’t stick at murder,’ I muttered morosely, picking up the evening post and tossing it aside again without a glance. ‘Japp ought to deal with crime gangs himself.’

Poirot surveyed me cautiously, his letter still in hand. ‘I don’t suppose,’ he said gently, ‘that you yourself have had any recent communications with the London Syndicate?’

That was far too close to the mark. Really, Poirot was a deuce for knowing things!

‘No,’ I said truthfully. ‘But I do think you ought to be more careful.’

Poirot picked up the newspaper I had flung away and neatly laid it on the table. He turned to me where I sat and said kindly, ‘I see you are not in l’humeur for this discussion tonight. It is well, my friend; I say no more. But I did not sign up for the profession of criminal detection to stand on the sidelines while it carries on under my nose, mon ami! Mine is not the soft job, though it rests entirely on the ingenuity of little grey cells and not on the brawn. And,’ he added grandiloquently, ‘Beware to the criminal who underestimates the skill of Hercule Poirot.’

* * * * *

I won’t elaborate on most of the following day, which was full of tedious broodings. As much as I didn’t want Poirot involved with whatever Mauta was planning, neither did I want them to have free reign in the neighbourhood. I decided that I didn’t have enough information to give to the police– not the sort that they would take seriously. And so I opted to pay another evening visit to Hodgkins, which would give me an excuse to investigate on the spot again later. Having been warned, I could be safely on my guard.

Or so I thought.

I met no one in the flats until I staggered to the door marked 56B, around midnight. I could not even fumble for my key. I just managed to press the doorbell, and as my friend opened the door and uttered a cry at the sight of me, I collapsed.

* * * * *

The first thing I noticed when I came to was the sound of dripping water and a hum of intense and agonized muttering. My eyes opened to the somewhat unfocused sight of Poirot bent over me, wringing a washcloth in an apparent frenzy of worry.

‘Do not move, mon ami,’ came his voice, low and hushed. I felt the washcloth cool against my head. ‘Sacré tonnerres! But what has happened, my poor friend? You are injured from head to foot!’

Stirring a little in spite of his command, I realized I was lying on the sitting room couch– how I got there, I know not– and Poirot was now cautiously dabbing at my forehead. The washcloth showed signs of red when he did so.

‘The doctor will be here with all speed,’ he murmured. ‘But sapristi, mon cher, what has happened?’

I took a deep breath and coughed a little. Poirot instantly produced a cup of water (seemingly out of thin air) and held it to my lips. When I had drunk a little, I found my voice.

‘Mauta,’ I croaked. Slowly and painful, I got my story told: the torch-light at the old warehouse yesterday; the sound of a cry for help; the first attack by the Indian hooligans; my decision to keep the details back for fear that Poirot would immerse himself in the case. I also recounted all that I could remember of tonight’s second and worse attack, including the hard punch to the face I’d managed to deliver to one of the gang before I was overwhelmed and pummeled, and the many new and ugly threats they made to Poirot’s person if either of us dared to show our face at that location tomorrow evening.

When I looked at Poirot again, his brow was black with rage. He began to hastily unbutton and roll up my shirt sleeves, my jacket having been discarded previously, and examined my arms. His hands were gentle despite his obvious fury. How much of that fury was directed toward me for foolish conduct, I wondered.

‘You are bruised badly… nom d’un nom d’un nom, Hastings,’ (and here his voice rose) ‘you should have told me! You cannot take on a force of this kind single-handedly!’

‘Neither can you,’ I muttered, a little annoyed. ‘And you would have done so. I daresay you will yet.’

Shaking his head sadly, Poirot reached for the basin of water again and wrung the washcloth. Taking my rather swollen and filthy right hand gingerly in his own tiny, immaculately-groomed one, he again uttered some Gallic oath at the state of it as he scrubbed at the purple and brownish marks as firmly as he dared. I winced a little.

‘The doctor will see if anything is broken or sprained,’ said Poirot in an odd sort of voice. I wondered if he was planning to keep me confined to my own rooms indefinitely until he had landed every member of Mauta in jail. His eyes were alight with that gleam I knew well, and he looked firm and resolute.

‘Tomorrow evening,’ he said, more to himself than to me. ‘Yes, in spite of themselves, they have given away their game.’

‘No,’ I cried, trying feebly to spring forward, only to be firmly pushed down again onto the cushions by Poirot. ‘You can’t. Mauta meets opposition with murder. Ten to one they meant for you to come after them, and you’re playing into their hands. You can’t…’

‘Calm yourself, cher ami,’ said Poirot soothingly, and patted my shoulder. ‘I will enlist some of Japp’s brave and clever men, and then this gang will have a strong force arrayed against them. I will phone our friend the Chief Inspector yet this evening– after all, I have yet to reply to his correspondence from yesterday.’ He shook a patronizing finger at me. ‘The grey cells, they will arrange everything! Do not fear any longer. Here you will stay and recover, and leave these heartless brutes to others.’

‘And you?’ I said, closing my eyes again and suddenly feeling very tired. ‘You’ll stay here tomorrow, too, and not go after them?’

Poirot did not answer. I opened my eyes again with suspicion, and Poirot merely carried on tending to the cuts and bruises on my arms and hands, innocently ignoring my question.

Dash it all, that man is infuriating!!

* * * * *

The next morning I woke early, aching all over and sporting a bandaged hand. On the previous night, Poirot had bound the doctor to secrecy, and I understand that after it was determined that I had miraculously avoided any broken bones, the two of them conferred while I dozed under a strong painkiller.

After I had bathed away a second night of remaining grime, I returned unsteadily to my room to discover a set of casual and comfortable clothing and a dressing gown laid out for me, folded as neatly and crisply as if they’d been cut from paper. This pointed gesture was clearly Poirot’s way of telling me that I wasn’t going anywhere today.

Poirot was seated at the table, sipping at a noxious cup of chocolate and scanning the newspaper. At my appearance, he leapt up and escorted me to the table, where he had prepared omelettes. I was relieved to see that he’d also provided a cup of tea.

‘Eat, my friend,’ he said energetically, pulling out my chair. ‘You will need to regain your strength. But today, you shall rest and cast aside worry.’ He made a characteristic gesture of supreme confidence. ‘All shall be well. I have said it, and parbleu, I am never wrong!’

I obliged him, and having eaten I returned to bed, limping a little, and slept off and on most of the day. But my waking hours were, despite Poirot’s reassurances, plagued with growing doubt and anxiety. All the facts pointed to a drug-smuggling operation taking place tonight at or near the warehouse. Poirot would surely be on the spot, and Mauta was cunning. They had caught me off-guard not once, but twice! I flushed angrily to think of it. Poirot was out of his depth this time, but his pride and stubbornness were legendary. Worse, he seemed to be taking the attacks on me as a personal insult.

‘They think they can threaten me, hein, and attack my poor friend comme ça! We shall see.’ When I tired of watching his pacing and gesticulations, punctuated with much incoherent French, I settled down in my armchair and closed my eyes, trying to decide what to do if Poirot were to leave the flat tonight.

‘You will stay, Hastings,’ he had insisted in no uncertain terms. ‘You will not play the Prodigal Son this evening. Trust Poirot.’ My little friend might be brilliant, but in view of the matter being rather personal, I was not sure I could trust his judgment in this.

And so, after dinner that evening, when Poirot made a rather elaborate pretense of going to bed early and insisted that I prepare to do the same, I obediently got myself ready. Poirot extinguished every light in the flat and practically pushed me into my bedroom, shutting the door with a click. I got into bed reluctantly, and felt a wave of tiredness overwhelm me. No, falling asleep would never do. Rising, I strode back and forth, fumbling silently in the dark for a change of clothes. I finished dressing properly, and perhaps half an hour had elapsed when I heard Poirot stirring somewhere in the flat. The sound of keys… yes, he was definitely preparing to leave. The moment I heard the front door softly open and close again, I came out into the hallway. Pausing a minute, I then stole out of the door after him.

I arrived on the ground floor as Poirot was exiting the glass doors of Whitehaven Mansions. Taking the utmost care to stay well out of sight, which did involve much stopping and ducking, I reached the front doors myself. Poirot had stopped in front of the building along the street, and was evidently trying to hail a cab. When I thought he was well distracted, I slipped outside through the door without a sound and quickly slid behind a concrete column. What the devil did he need a taxi for? The warehouse was just a few blocks away. Perhaps he was planning to meet Inspector Japp somewhere nearby first. That sort of thing should have been organized earlier, I thought. No time to dawdle at this hour, when the crime was imminent, perhaps even happening as we stood there!

In a few moments, a cab had pulled up. I leaned out as far as I could to hear Poirot say to the driver, before entering: ‘Alloway Park, East End, please, driver.’ He got in and away they went, as I stood there with my jaw dropped.

Poirot was headed clear across town! Surely he could not misunderstood the place where I had told him I was attacked. Had I mistaken his intentions tonight– had he really left Mauta to the police as I’d hoped, and was heading out now on some private outing of his own? That did not seem to agree with his secrecy this evening, nor his usual love of being on the spot to apprehend a criminal. And Alloway Park was a dingy little area on the outskirts of London with virtually nothing around, certainly nothing that would be of any social interest to my friend. I was baffled.

My plan, of course, had been to follow him. I hesitated: should I follow him or head over to the warehouse myself? I came to the edge of the sidewalk and hailed a cab of my own. Hesitating a few moments, I said, “Alloway Park, East End,” and got in.

* * * * *

My cab was several minutes behind Poirot’s, which was just as well, as I certainly didn’t want him to catch on to the fact of my proximity. The lights of London whirled by, on and on. I was completely nonplussed, but nonetheless relieved that Poirot was heading away from that dangerous Indian gang lurking in our own backyard. Then again, this was Poirot; you can never quite rule out mischief on his end.

Alloway Park covered a large, unkempt, and weedy area which looked sad and forlorn in the darkening dusk. When we stopped, I paid the taxi driver and he pulled off again. The occasional car came and went along the dirt road that featured a shabby news stand (now closed), a little tobacconist, and a few storage sheds. Trees and grassy patches completed the disorganized jumble. I cast my eyes about in the growing darkness for any sign of Poirot. I thought I noticed a few cars parked further down the street, not far from…

An old warehouse!

It could not be coincidence, surely. And, just as surely, Poirot could not have mistaken the place I told him about? But whatever he was up to, there was no doubt that I would find him in that area. I decided to forego the street and cut across a little wooded, grassy area to make more directly for the building, stumbling a little on sore limbs, my breath coming fast.

About halfway there, for the third time in three days, I looked up to see men coming out of the shadows into my path. There were only two this time. I stopped, completely confused and too weary to take the defensive, as they became visible. They were bare-headed and fair, and as I somehow expected, did not look happy to see me. The taller of the two came right up to my face, as the other gripped my arm painfully. I found myself looking into cold, hateful eyes, feeling a keen and painful déjà vu. Good Lord, was every criminal across London intent on attacking me for going about my own business?

‘You are a long way from home, Captain Hastings,’ the man before me sneered, and I started upon hearing my name.

‘I don’t know who you are. You’ve nothing to do with me,’ I stammered. There was no energy in me to fight. ‘I’m looking for a friend of mine.’

The man stiffened, and he gave an uneasy glance at his companion who was holding me. Suddenly I feared that I had given Poirot away, but then a rustle several yards away made us turn our heads, and a familiar voice said, ‘And you have found him, mon ami.’

Amazed, we stared at the little man who emerged from the trees. The man who held my arm gripped me a little tighter, and Poirot said sharply: ‘I will thank you to unhand my friend, s’il vous plaît. He has incurred sufficient damaged as of late and I would prefer that he be spared further blemish.’

The tall man with the cold eyes advanced a step, and Poirot held out his hand out arrestingly. ‘Further violence will not avail you. The area is surrounded. Your friends are, at this very moment, apprehended by the police at your base of operations. Next it will be your turn. There is no escape.’

The man stopped and turned to look at his companion and me, hesitating. More figures appeared, small in the distance, training electric torches in our direction. A thundercloud passed over the man’s face– such a familiar face, furious and desperate– as he aimed a heavy blow against the back of my head. The last thing I saw before I fell was the shocking sight of Poirot, running toward us…

* * * * *

‘Ah! My dear Hastings!’ Poirot ejaculated. ‘The imbecilities you have committed! Oh, but you are a loyal friend. You use your grey cells not at all, but what a beautiful nature you have.’ And he beamed affectionately on me.

I declined to argue the point, instead shifting the pack of ice I held to my aching head as I reclined on our sitting room couch. ‘But what happened? Why did you go across town? What about–’

‘Slowly, my friend,’ he said. ‘Did I not tell you two days ago that I had received communications from Japp about the London Syndicate? He had received a tip-off that the organization in question might be attempting, in the near future, to conduct smuggling operations near a certain warehouse on the outskirts of the East End. I simply went there with the police to apprehend our culprits.’

Confusion was writ large on my face. ‘But, Mauta– you’ve let them get away with their crime, right here in our neighbourhood?’

‘No, mon ami, you do not understand. Mauta had no crime operations in our neighbourhood. In fact, Mauta has never been here at all.’

I stared. Poirot lit one of his tiny Russian cigarettes, settled more comfortably into his armchair, and resumed his speech.

‘In light of Japp’s tip, it seemed an interesting coincidence that these thugs you’ve been encountering were so eager to draw the gaze of Poirot to a local warehouse in our own backyard. It was possible that the smuggling was indeed to happen here, and Japp’s informer was mistaken or lying. But why announce the fact with violent attacks and threats? And they could not seriously think that you were walking home along that route that evening because you suspected anything.’

‘But,’ I stammered, ‘that cry for help that I heard–’

‘–Was merely part of their plan,’ said Poirot gently. ‘To draw you across the street to the warehouse. They have studied your psychology, mon ami, and knew that you would rush to the aid of one in distress. They assumed you would tell me what had happened on that Wednesday evening, to interest me in that vicinity and perhaps to help the owner of that mysterious voice calling for help. But never had it occurred to them that you would refuse to tell me anything in order to protect me! No, they do not know your nature as I do. When they saw no trace of me the following day around the warehouse, they correctly guessed that you had not told me, but would be back yourself later that Thursday evening. It was imperative that the message be impressed upon me before Friday, in order to draw my attention as far away as possible from the real operation in the East End.’ He made a face of angry disgust. ‘They made sure that your injuries would be too serious to be hidden or overlooked this time. Ma foi, the animals. But you were quite right when you told me yesterday not to go to our local warehouse tonight, that they meant to draw me there– however, it was not to attack, but to misdirect.’

‘Do you mean,’ I cried, ‘that the gang that attacked me wasn’t Mauta, but the London Syndicate, and you knew it?’

‘Précisément. Your deduction awakens at last.’

‘It seems unbelievable,’ I mused, bewildered. ‘I was sure that those men in the alley were of an Indian family… and the way they spoke, and the insignia…’

“Bah! It is child’s play to dress up like members of a small and obscure Indian gang. Head-coverings, accents, little badges. They may fool the eye, but not the mind.’ Poirot smiled at me.

A thought struck me. ‘Yet– yes, I’m almost sure– tonight, I thought I recognized the man who found me at the Alloway warehouse. But he was fair, not dark.’

‘Ah! You come to it. I shall tell you how I came to be sure of the truth of the matter. The other night, I attended to the cuts and bruises on your arms and hands. The bruises on your arms had a distinctive appearance, but your right hand, used to strike one of the gang members in the face, had discolouration that could not be accounted for. You did not seem to have any other marks of that brownish tinge on your face or arms. I pray that you will forgive me for scrubbing those marks on your hand a little more enthusiastically than I otherwise should have done.’ The very memory made me cringe. ‘But, voilà, those brown marks came off at once! They were not traces of dirt or mud, but had more of an oily texture and a distinctive odour. I have seen it before– it was face paint! Le maquillage.’

Dumbfounded, I said: ‘That was quite a remarkable guess, at any rate, and a bit of a long shot!’

‘Not at all. For not one moment had I believed that Mauta was anywhere in the vicinity. In addition to their rare public appearances in general, there were other indications. As you have so admirably pointed out, Mauta does not leave those who threaten their interests alive. They would have almost certainly killed you. The attacks you suffered were more in line with the tactics of the London Syndicate– often violent, but seldom deadly.’

Poirot laid down his cigarette and regarded me pityingly over tented fingers.

‘Then there were the obvious warnings and threats that seemed designed to draw attention away from the East End warehouse, as I have mentioned. I deduced that the gang you met could not have been Mauta at all, but must be members of the London Syndicate, in rather obvious disguise. I was not at all surprised to find the brown smudges on your hand, my friend.

‘Ah! But they are clever. They mean to send the police and Poirot to chase the wild goose, their old rival Mauta! They both draw attention away from themselves and commit assault in the guise of their competitors. But they defeat themselves. Once I suspected their plan, I also knew that they had handed me the final piece of the puzzle first presented to Japp– the time of the smuggling operations at the East End warehouse. This Friday evening! Alors, we go and make our arrests.’

For a moment, words seemed to fail me. Then I said, ‘I wish I’d known about Japp’s message to you on Wednesday about the second warehouse. It might have put me on the right track.’

‘If you recall, I had wanted to tell you, Hastings. Indeed, you are always of the greatest assistance to me! In this matter, too, you nonetheless provided the vital clues. But you were preoccupied with your first encounter with the rogues, and intent on your own little deception. At any rate, there were other indications sufficient to awaken you to the truth if you’d had eyes to see them; though I do not blame you, what with the numerous hits on the head you have sustained. One cannot expect the brain to function at its best in such a case. Ah, if only you would trust your friend and his grey cells, cher ami!’

Sensitive to what must have been a defeated look on my face, Poirot rose and crossed the room to me. His hand rested comfortingly on my shoulder.

‘Perhaps, after all, I should have stayed in the flat this evening with you, and left all to Japp,’ mused Poirot. ‘My enjoyment of my own denouement, it has failed me this time. I did not think you would be so hot-headed as to have my taxi followed. If you went out at all, I expected you to go to our neighbourhood warehouse, where I knew nothing would happen. There, also, I failed in method! And to limp around in the dark with dangerous men about, Hastings!’ He shook his head, and his manner softened. ‘But you would not let me go out alone, hein? No, that would not be like you.’

I looked up at him, and did a double take. So fastidious was Poirot about spotlessness of appearance that at close quarters I noticed, at once, a strange and discoloured streak on his right cheek.

‘Poirot,’ I exclaimed. ‘You’re injured.’

He waved his hand airily. ‘Ce n’est rien, a scratch only. Regard my friend Hastings, who is beaten into the ground, shout indignantly about a little cut! It does not hurt. It only ruins the symmetry of the face, which is indeed far more painful to my sensibilities.’ His expression was so distraught over this detail that I was tempted to laugh.

But then something else occurred to me. ‘I saw you running,’ I said slowly, the memory returning. ‘Right before I was hit on the head. You were running toward us.’

Poirot exhaled. ‘It is true. I am not in the running habit, I think is what you mean. I am also not in the habit of brandishing my stick, with its heavy knob, at gang members and knocking them senseless. Nonetheless.’ He shrugged.

‘Poirot,’ I cried again, stupefied.

‘I lost my temper tonight. It does not happen often. There was a small scuffle. Only once before have I used my walking stick in such a fashion. A young child, a girl… a daughter… was in imminent peril from a desperate and dangerous assailant.’ A wistful, faraway look stole over his countenance.

‘Three times, mon ami,’ he said, looking down at me with sad and pained eyes. ‘Three times they dared to assault you! One does not commit such acts against one’s fellow men, but against one of such an innocent and trusting nature…’ His voice rang with steel. ‘Those are the most wicked crimes of all!’

Regaining his composure, he sighed again and added: ‘Why does the father run to reach the prodigal? The son has been in dire straits. The fear is upon the father. He loves his son and wants to bring him home again.’

And with that, he turned and left the room. Moved, I looked after his retreating and deceptively small figure. In truth, I thought, never was there such a force of nature to be reckoned with as Hercule Poirot.

Of twin sisters and seeing double

Two Poirot novels prominently feature twin sisters as a central point of the mystery: The Murder on the Links and Elephants Can Remember. In other words, Christie’s second published Poirot novel, and her-second-to-last-published Poirot novel. (2, 2, 2…) The twin sisters of The Murder on the Links, as Poirot readers know, feature largely in the life and the future of Hastings. He marries “Cinderella” a.k.a. Dulcie Duveen, whose sister Bella marries Jack Renauld. Because of the South American interests of the Renauld family, the latter couple inevitably relocates there, and Hastings and Dulcie decide to join them as well to start a ranch.

There’s a strange little passage in Peril at End House when, as Poirot is getting on Hastings’ nerves, the following dialog ensues.

‘Do you suppose I’d have made a success of my ranch out in the Argentine if I was the kind of credulous fool you make out?’

‘Do not enrage yourself, mon ami. You have made a great success of it– you and your wife.’

‘Bella,’ I said, ‘always goes by judgment.’

‘She is as wise as she is charming,’ said Poirot.

Um, have Hastings and Poirot forgotten to which twin sister Hastings is married?

I don’t know if this has been written about or explained by Agatha Christie or anyone else, but it seems most likely that it is a mere mistake. If one is determined to resolve the problem “within the canon,” it’s just possible, I suppose, that Hastings’ sister-in-law is known to be the business brain behind all the entrepreneurial affairs of the family in South America, and he’s changing the subject to impress upon Poirot that even she trusts his judgment implicitly. But that is not really the context of the conversation. It’s a very bizarre moment.

It’s additionally funny– and weird– because in the television series, of course, one of the sisters is cut out altogether and Hastings and Bella Duveen do end up together!

A cake for Agatha Christie’s 125th

Back in September, Agatha Christie’s Twitter put a sort of “cake challenge” out there: make a cake in celebration of Agatha Christie’s 125th. No need to ask twice– I make fan art on the most ridiculously slight of provocations. And I’d never tried making fan art via cake. The very prospect sounded so insanely nerdy I just had to try. Anyway, CAKE!

It would have to be something Poirot-esque. I had used edible marker on fondant for cookies once or twice in the past, and I’d used gel food coloring for tinting molded cookies, but I’d never tried anything like a portrait in gel coloring on fondant, nor had I made decorative, edible flowers. I decided to try both. You also need to know that I am terrible at baking…

In spite of me, the cake made it out of the pan more-or-less successfully. It was (necessarily) square-shaped, in keeping with the Poirot motif. With a great deal of frustration I sliced the square cake in half and iced it together again, finally breathing a sigh of relief that the complicated, unpredictable, and aggravating part was over. Now I just had to paint the portrait and sculpt some flowers and stuff, which as far as I’m concerned is infinitely easier than fighting with cake ingredients.

The white fondant was rolled out and trimmed to be a little smaller than the cake top. The picture on which I was basing my image was obtained from the episode Death in the Clouds. Gel food coloring was mixed with vodka to paint on the portrait. (The Countess Rossakoff approves.) The actual painting part was a sort of learn-as-you-go experience. I cautiously added thin layers and built it up gradually. And as Poirot slowly came into focus, I shuddered to think how positively mental Suchet would think me if he ever found out that he was being painted in costume, onto a piece of fondant, with vodka… and for no particular reason except for what was essentially a Twitter dare.

Oh well.

I found a tutorial on the internet for the creation of molded poppies, but used fondant instead of gum paste just to make life more interesting. (Poppies are a flower I identify with Poirot. If you decide to use this tutorial, intrepid reader, follow their instructions as written!) An additional amount of my white fondant was heavily tinted, turning my hands bright red, and I managed to get some poppies made. The frilly centers turned out nicely and helped to give the false impression that I knew what I was doing. Long, thin, green poppy stems were also rolled out.

The fondant portrait was eventually anchored to the center of the cake with some sort of gel icing. The original plan was to have the green poppy stems attached to the flowers right on the cake itself, but it suddenly seemed like a better idea to add a thin green “stem” border all the way around the portrait. A second border was added of tiny silver candy balls, vaguely reminiscent of Poirot’s brooch, or whatever. They looked bling-y, anyway. A couple of poppies were added to wherever they might fit on top of the cake. I had a little bit of my red fondant left over, so I thought I’d make a “125” to attach somewhere onto the cake. I didn’t own any number cutters for fondant or anything handy like that, so I cut them out by hand and gel-glued them to the front side of the cake.

The final poppy, which wouldn’t have fit onto the cake anyway, I arranged decoratively in front of the cake (as though that was what I meant to do all along, ha) with its stem, which is actually not even attached to the flower. I forged Christie’s autograph onto a stray piece of fondant using edible marker so that, just maybe, the theme of the cake might be slightly more obvious.

Voilà… cake!

The cake was finished just before Christie’s birthday, and it seemed like a good idea to take it to our local library, an institution to which I owe a great debt and where I had first blasted through a large number of Christie’s works. My husband called the library and asked if they knew it was Christie’s birthday. They didn’t. He told them to be on the lookout for cake. We dropped it off that afternoon, the 15th of September.

The library (which is a fairly small one) got into the spirit of the thing and posted on their Facebook page that they had cake, inviting people to come celebrate Dame Agatha’s birthday. They apparently made tea and set the cake out with stacks of Christie books to encourage visitors to check them out. We missed out on the party, but it seemed to have been a sweet little affair. I was told later that when they were cutting the cake, they carefully cut around Poirot first to avoid damaging the portrait. It’s hard to blame them– attempts to stick a knife into Poirot are not going to end well. But the cake did completely disappear in the end.

Later they sent me a cute little thank-you card. 🙂

The only moment of cringe once the cake was done was the comment of one gentleman on the library Facebook page, who, upon seeing the cake, helpfully informed us all that Agatha Christie was, in fact, a woman. OH, did I cringe. Several wincing cringes. Someone at the library set him straight though. 😉

The theology of The A.B.C. Murders

In a previous post entitled “The theology of the Clapham Cook,” I discussed some interesting script choices in that first episode; namely, that a passage of Scripture is read by a background character which actually encapsulates the entire theme of the episode. Something similar happens in the television adaptation of The A.B.C. Murders, coupled with a few religious artifacts of note.

Those interested in fashion particularly notice the amazing wardrobe skills on display in a series like Poirot; car enthusiasts are apt to point out the vintage cars. Well, art and theology are two special hobbies of mine, and they inevitably jump out at me in viewings of the show. Sometimes this takes the form of vintage devotional items, which I always notice with great interest, and there happen to be some in this episode.

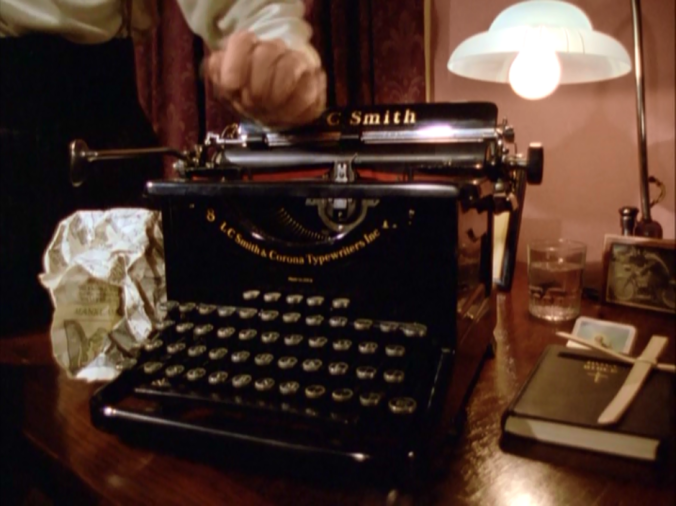

There is a flashback scene in the denouement in which Cust is receiving his new typewriter. Sitting on his little table are a few personal objects and knick-knacks, including three devotional items: a Bible, a palm cross, and what looks like a little picture or prayer card.

A Bible shows up at least twice more around Cust: in his Doncaster hotel room, and in the prison cell, where he is reading it. (More on that later.) The palm cross is an interesting prop choice– it is a simple, traditional Lenten and Easter craft made from a folded blade of palm frond, sometimes from the palms used on Palm Sunday. It is a symbol of suffering, martyrdom, and future glory. It initially stood out to me because the scene takes place at a different time of year than you’d usually see palm crosses about.

The prayer card or picture is just barely visible, but due to the universal iconography of the figure, I am about 99% sure that there is a picture of St. Jude on it. That particular apostle has for many years, and certainly by the 1930s, been depicted in a white robe with a green drape over one shoulder, holding a staff or club (referencing his martyrdom), having a small flame over his head, and holding an image of Christ. The last two objects are indeterminate in the shot, but the rest are clearly visible. Compare for yourself, intrepid blog reader, whether the card in the shot above is likely to be a picture of St. Jude…

“Fine, well spotted, but who cares?” you say.

It’s merely the interesting coincidence that a glance through the hagiography of St. Jude happens to show some unusual points of connection with A.B. Cust. The Catholic Church represents him as the patron saint of lost causes, things despaired of, and hopeless cases. That association has to do with the fact that St. Jude (or Judas) shares the name of another apostle, Judas Iscariot, the traitor to Jesus. The unfortunate similarity of name, and the subsequent oft-mistaken identity, apparently resulted in a sort of neglect and forgetting of St. Jude by many in the Church, and so he is regarded as a beacon of hope for things despaired of and forgotten. Does that does not ring a bell with the pitiful, forgotten, hapless Mr. Cust– who is not, in fact, the A.B.C. letter-writer, but is presented as the murderer to the police in a case of mistaken identity?

But wait, there’s more. 😉

In his prison cell, just as Poirot enters, we can hear Cust reading from the Bible– to be specific, the Beatitudes, from the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 5. “And He taught them, saying: ‘Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted. Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit–”

The Beatitudes are a well-known Christian text that offer words of comfort and blessing by Christ to the suffering, wrongly oppressed and accused, and persecuted. Again, this fits Cust to a tee, and the reading here at least was certainly not coincidental, but chosen for that purpose.

But in other interesting details of chance: the staff or club held by St. Jude signifies that he was martyred by being bludgeoned to death, which is how the murderer commits two of his deeds, including the “main” murder of his brother. And also, take notice where Cust suddenly stops in his reading. “For they shall inherit…” Unknowingly, Cust utters the real motive for the crime of which he is unjustly accused– Franklin Clarke kills in order to inherit his brother’s fortune!

“’Course, it might be a coincidence.”

Oh, who am I kidding, of course I do! 😉

I don’t pretend that the particular choice of devotional items was intentional, in those particulars, for the episode, but how very well it all hangs together, n’est-ce pas?

Thirteen at Dinner humor…

Hypochondria, and patronizing Poirot to your peril (a.k.a. “Hastings gets told”)

A couple of weeks ago I blogged about the paternalistic tendency of Poirot to organize other people’s lives for them, and the condescending way this sometimes played out in his interactions with Hastings in the series.

What happens when a character dares to do the same with Poirot? Much entertainment! In short, whenever there is fuss, Hastings invariably gets told off.

In the books, Poirot sometimes allows himself to be condescended to by behaving more naively “foreign” than he really is, to deceive others in the course of an investigation. For all his vanity, he is willing to buy success by (temporarily) enduring scorn, or being thought a mountebank.

‘It is true that I can speak the exact, the idiomatic English. But, my friend, to speak the broken English is an enormous asset. It leads people to despise you. They say– a foreigner– he can’t even speak English properly. It is not my policy to terrify people– instead I invite their gentle ridicule. Also I boast! An Englishman he says often, “A fellow who thinks as much of himself as that cannot be worth much.” That is the English point of view. It is not at all true. And so, you see, I put people off their guard.’

-Three Act Tragedy

Not much of this particular quality makes itself blatant in the course of the series, but other forms of condescension present themselves– sometimes welcome, and sometimes not.

Hypochondria is just one of Poirot’s irritating-but-much-loved traits, and one particular expression of his vanity. Generally, he is only too delighted to be fussed over. But there are various scenarios in which he dislikes the attentions, such as when his personal dignity is affronted, or when being fussed over prevents him from doing what he would rather be doing (such as investigating), or when blatant opportunists want to take advantage of him. In those situations, coddlers, fussers, and patronizers beware. Unless you’re Miss Lemon, who can get away with anything.

Classic examples in The Mystery of Hunter’s Lodge…

Hastings: “You get back into bed now. You can leave this to me.”

Poirot: “Comment?”

Hastings: “This investigation. You can leave it to me. I’ll report back to you, of course. I know these people, Poirot. I’ve got one or two ideas already.”

Poirot: “What are these ideas, Hastings?”

Hastings (holding up a finger): “You just relax.”

Poirot: “Hastings, will you please stop tapping your nose in that theatrical manner and tell me all that you know!”

Likewise, he later snaps at Japp who asks him if shouldn’t be in bed: “Possibly, but please, do not fuss!” But he happily accepts blackberry tea from a paternal railway operator as he wheedles information out of him for the sake of the case.

Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan is comprehensive in showing how Poirot deals with “fusses” of both the patronizing and non-patronizing variety. The first time he encounters someone playing the newspaper game of hunting for “Lucky Len,” he is pleased at being recognized as someone whose face has often been in the papers (later to be disillusioned). But when Mr. Opalsen uses Poirot’s presence at his play for the sake of newspaper publicity, he is outraged and takes his revenge by later getting the otherwise innocent Mr. Opalsen arrested. Comparatively, in The A.B.C. Murders, Poirot receives somewhat unflattering newspaper coverage to Hastings’ concern, but does not himself seem to mind, as he hopes it will help the murderer relax his guard.

Jewel Robbery suggests something else of Hastings’ very occasional patronizing air. Extremely laid-back compared to his ever-interfering and micro-organizing friend, Hastings only seems to present this attitude in the case of serious illness or, notably, faced with the terrifying prospect of Miss Lemon coming down on him like a ton of bricks for dereliction of duty.

Hastings: “This was meant to be a rest, you know. Heaven knows what Miss Lemon’s going to say when she arrives.”

Miss Lemon (arriving later and meeting Hastings with a snarl): “I thought this was meant to be a holiday, Captain Hastings. I’ll talk to you later.”

Then there’s Evil Under the Sun, in which the script writers decided to invent the pretext of a health concern for sending Poirot and Hastings off to the Sandy Cove Hotel. While Poirot sits in leisure, conversely moaning pitifully and then complaining that everyone knows he’s ill, Miss Lemon is at her most sternly efficient. Call it maternal rather than paternal– she’s in league with the doctor and brooks no denial as she arranges for the pair to head to the island without a word of consent from either of them. Undoubtably, Hastings’ subsequent hovering at the hotel is due largely to the fear of the wrath of Miss Lemon.

Hastings: “How are you feeling, Poirot? Not too tired after the journey?”

Poirot: “Hastings, I am recovered, I am not the invalid. There’s no need to act like a mother chicken.”

Later, we have further evidence of what lies behind Hastings’ concern…

Hastings: “So, how are you feeling, Poirot?”

Poirot: “Do you refer to my health, Hastings, or to my feelings concerning the events on this island to which I am confined?”

Hastings: “Well, both, really. I’m going to have to phone Miss Lemon today. She wanted a daily report.”

Poirot: “You may tell to her that I am not sure.”

Miss Lemon eventually shows up, grumbling: “He was meant to be having a rest.” But as Christie readers (and viewers) know, Poirot does not actually need coddling to get better– just opportunities to exercise the little grey cells, a tisane or two, and a good boost to the ego. The opening scenes of The Third Floor Flat feature more of Miss Lemon making a fuss.

Miss Lemon: “Ah– Mr. Poirot. You’ve only done seven minutes. You’ll never cure your cold if you don’t obey the instructions.”

Poirot: “I can’t imagine a method so undignified can cure anything, Miss Lemon. And now also I have the backache, eh!”

Hastings doesn’t get told here, but he gets told later when Poirot blames riding in the Lagonda for his “present malady.” #BlameHastings

Sure enough, the stimulation of the case soon has him on his feet again: “Poirot does not have colds, Miss Lemon. It is well-known that Poirot scorns all but the gravest afflictions.”

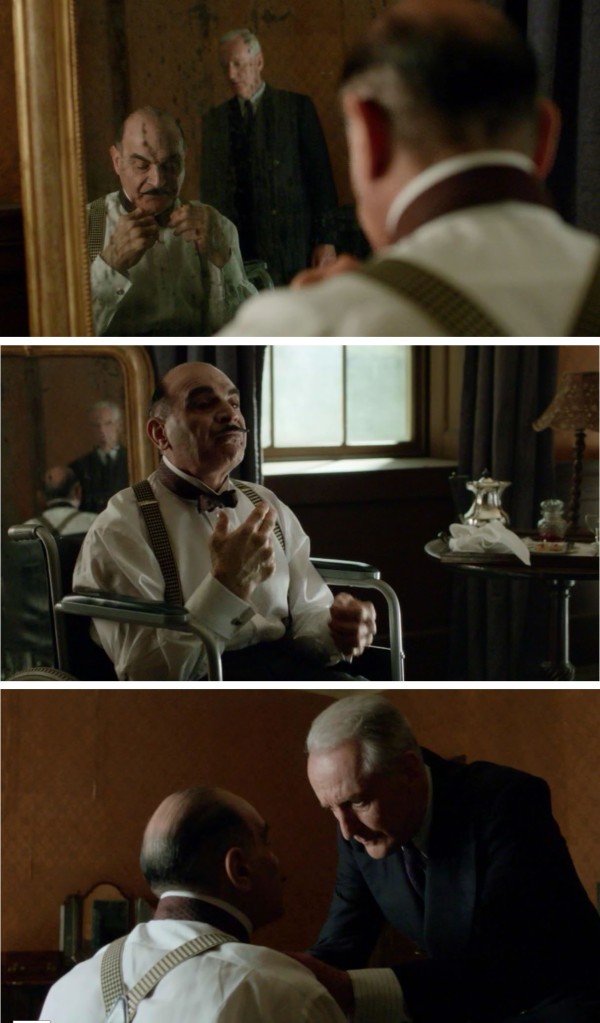

Then, again, there’s Curtain. So many of these themes that wind through the Poirot canon come full circle in that book and episode. In the final story, Poirot is faced with the ultimate in coddling, and expresses his disgust openly at being treated like a child– although some of it is a ruse. And of course, he’s forever howling at Hastings, alternately for his stubbornness, his denseness, or even his inability to coddle properly.

One thing is not a ruse: Poirot’s arthritis. In the critical scene of Hastings’ confession to Poirot of his nearly-attempted murder, something is happening throughout the course of the conversation. It is not commented on, but in many ways, it is just as meaningful and gut-wrenching as the dialog. Poirot is sitting in front of an ancient mirror, attempting to tie his perfect bow tie. He can’t quite manage it. Finally, wordlessly, he appeals to Hastings for help– the one whose tie he had been straightening for so many years.

Poirot and Hastings, from Murder on the Links – painting

Most of my fan art whatsits are quite small (what would one do with a roomful of large, Poirot-themed canvases?) and sketch-like. The biggest exception would be that set of 39 miniature painted books, which are small but finished. When faced with the prospect of donating a piece of Poirot fan art to a good cause, however, I thought it would be best to make something new which could be just a bit bigger than usual and a little more polished.

This is an acrylic painting on a gessoed hardboard panel, 12″x12″. It is almost the size of a record album and has a strangely similar feel. 🙂 I used the same image from Murder on the Links that I used for the miniature book cover– I love the bright, impressionistic feel of that particular moment. My own tendency is to smooth out brushstrokes in my paintings, but this time I tried to maintain a bit of that sense of impressionism in the greenery of the background.

The London Syndicate, Chapter 1

Preface / Fair Warning

I have a confession to make: I write new Poirot stories. Don’t hate me. I know that such a move is regarded by many readers as everything from laziness to blasphemy. If it’s not your thing, feel free to utterly disregard. 🙂 For others of us, we’ve seen that the more a good author gives, the more fans seem to want and demand (see: Tolkien). Poor Agatha worked herself into the ground with 50-some years worth of Poirot stories for her fans, and even took it upon herself to definitely close the canon, and yet we find we want more. My consolation is that Sophie Hannah’s recent efforts at least prove that the Christie estate does not regard a sort of re-opening of canon to be utterly heretical. My goal has been to try to keep as closely as possible to the “voice” of Christie, and also to try my hand at her style of mystery-writing. I don’t own Poirot, Hastings, Japp, and any other Christie characters that might pop up, nor do I profit in any way from these stories.

This particular series of stories, still in progress, exists under the title The London Syndicate. The LS is a criminal organization and the stories follow various exploits connected with them. It seemed to me that after Poirot had proven his mettle in London, it behooved the local criminal world to start taking him seriously enough to acknowledge the threat he posed to their operations. In this sense, the stories are somewhat in the spirit of The Big Four, though perhaps with a bit less– shall we say– exaggerated global drama?

I’m in the habit of deliberately conflating the books and the TV series when discussing Christie’s Poirot, and these stories are no different– I always attempt to be as consistent with both as possible, bringing them into unity. Close readers (and viewers) will notice that some details of the stories come exclusively from the books: aspects of the narrator’s internal monologue, Poirot’s green eyes, Miss Lemon missing in action when Hastings is on hand, and so on. Some details derive exclusively from the series: the setting in the 1930s at Whitehaven Mansions while Hastings is yet a bachelor, and aspects of the flat, for example. My series has one or two necessary anomalies; for instance, the events of The Big Four have already transpired despite the fact that Hastings is not yet married. But I’ve tried to keep these discrepancies to an absolute minimum. 🙂

Well, here goes…

* * * * *

The London Syndicate

Chapter 1: The Trophy

I was in the kitchen, brewing a late morning cup of tea, when the door opened with a bang.

‘Hastings!’ came the high, energetic voice, followed by the shuffling sound of a hat and coat hung up in the hall. Into the kitchen bustled Hercule Poirot, delight radiating from his face.

‘I have wonderful news, my friend,’ he cried, and before I could step aside he clasped me in a continental embrace. ‘They hate me, Hastings!’

Although completely unable to account for why being hated was a cause for such mirth, I was used to my little friend’s eccentricities. ‘Splendid, old boy,’ I said ironically as I extracted myself and added milk to my cup. ‘Who hates you now? You were meeting with Japp this morning, I know. Have you gotten on his nerves one time too many?’

Poirot did not seem to perceive my jest. He had obtained a tin of chamomile tea and was preparing a beverage of his own, humming jovially. ‘I have spent the morning at the police station, cross-examining a man by the name of Whitcombe, a major player in the Battersea Scandal.’ I nodded at the reference to Poirot’s latest successful case. ‘Japp informed me that Whitcombe had been double-crossed by his associates, and in the course of careful questioning, we have determined that he was working in league with a crime syndicate on a scale we had not dreamed of. Mon ami, I am disliked and feared by a most notorious criminal organization!’

And preening rapturously, he seated himself opposite me with his tea. I was torn between amusement at his incorrigible vanity, and a fair bit of alarm at the notion of dangerous criminals with a vendetta against my friend. Only Poirot would take this kind of announcement as nothing more than a supreme compliment to his stellar reputation!

‘For goodness’ sake, tell me about it,’ I pressed. ‘What did you learn from Whitcombe?’

Poirot carefully dabbed at his moustache and set down his cup. ‘The group is commonly known as the London Syndicate. It seems as though a number of crimes we had previously thought disconnected and isolated were, in fact, organized by this group. They deal in all manner of robbery, smuggling, fraud, kidnapping, tout imaginable. With one exception– they are not notorious murderers. While certain actors in their midst can be vicious in the extreme, they seem to frown upon murder as being insufficiently creative and subtle in achieving their ends. And, of course, it is bad for business. No, they are not fools.’ He stared dreamily into space.

It seemed prudent to interrupt his transports with a dose of reality. ‘All the same, Poirot, any dog will bite if sufficiently provoked. You can’t count on endless gentlemanly behaviour from that sort of outfit.’

‘No, my friend, you are right. We are not dealing with the bastion of human kindness. There is brutality. There are those in the Syndicate who collect symbols of conquest from their victims. And Whitcombe had the kindness to relay a few of their threats for my information.’ My eyebrows rose, and he went on: ‘Any gang will threaten, mon ami. That is simply par for the course, as you English with the golf mania would say. Me,’ he shrugged dismissively, ‘I have received threats before, and will again. It is part of the job. All the same, the notion of dealing with criminals who are artistes, who, in the name of le sport, do not wantonly murder… it is a most pleasing thought.’

I hardly shared Poirot’s views on sportsmanlike conduct, but I could see that my friend was in no state to be reasoned with. We retreated to the sitting room, Poirot to his desk and I to the sofa, and he began to sort through the morning post. Setting down three bills, he regarded a fourth envelope with some interest. He carefully slit it open with a silver paper knife set with a large, deep blue lapis cabochon.

‘Ah,’ he said with disappointment upon reading it. ‘It is another elderly lady who has mislaid her brooch. It has been missing for some time, and she decides at last to do something; quel dommage. Yet I very much fear,’ he said ruefully, casting a glance at his stack of bills, ‘that I must take this job.’

‘Well,’ I said laughing, ‘You may yet cross swords with your notorious criminals. In the meantime, there’s the daily grind to deal with– rich old ladies.’

After slitting open the rest of his mail and considering it indifferently, Poirot placed it in a neat stack on the desk and carefully repositioned his paper knife, with parallel accuracy, a little above the stack. He noted again the address of his lady correspondent, then rose immediately and headed toward the door.

‘I shall return forthwith, Hastings. This will not take long.’ And collecting his personal effects, he swept out again.

* * * * *

Several minutes later, I received some unexpected callers to the flat– two well-dressed young men, perhaps in their late twenties. They introduced themselves as Mr. Brian Westhelm and Mr. Matthew Carrington. I explained that Poirot was out, but that I could hear their concern on his behalf.

‘Pleased to meet you, Captain Hastings,’ said Westhelm, shaking my hand firmly. He was of medium height and weedy, with ash-blonde hair and freckles. He exhaled confidence and warmth, and I immediately took a liking to him.

‘Carrington and I are cousins. We’ve discussed our problem, and he recommended that we seek advice from M. Poirot.’ Matthew Carrington shook my hand in his turn. I could see the definite family resemblance: they had the same hair, freckles, and steel-grey eyes; but Carrington was stockier, and his eyes held a pronounced touch of far-off sadness.

I gestured them into the sitting room and asked about their trouble. Neither man sat, but Westhelm began at once.

‘It’s our aunt, you see. She had misplaced a rather valuable item of jewellery recently…’

‘Oh!’ I interrupted, striding over to Poirot’s desk and taking a seat. This sounded familiar. ‘And is the name of your aunt–’ (I picked up the stack of mail and scrutinized the lady’s name on the top envelope) ‘–Mrs. Adelaine Brooks?’

Both men, who had followed me to the desk, stared at me. For a moment I fancied that I had impressed them, but Carrington said, ‘No, not at all. Her name is Lady Margaret Westhelm.’

‘I see,’ I said, deflated. Tossing the stack of mail onto the desk again, I added, ‘Please continue.’

Mr. Westhelm cast a curious glance at the envelopes before resuming his discourse. ‘Lady Margaret was married to my father’s oldest brother. My cousin and I were calling on our aunt at Rathene Hall two weeks ago when she told us that she couldn’t seem to find her turquoise necklace. It was a valuable piece, set in gold, and one that I’ve seen countless times. Well, a few days ago I spoke to her on the phone, and she mentioned that she’d found it again– seems it was in her armoire the whole time. We went back for another visit and saw the necklace. Captain Hastings, I was sure that something was wrong with it. Auntie doesn’t have the best eyesight, but the necklace didn’t look quite right to me.’

‘I agreed,’ added Carrington, ‘and the two of us talked it over. I have an acquaintance in the neighbourhood who knows a thing or two about jewellery, and we brought him round to tea at Auntie’s that afternoon. Sure enough, as he was leaving, he confided to Brian and myself that the necklace was certainly not genuine.’ Now Carrington was staring at Poirot’s stack of mail, but with a more abstracted manner. He seemed to have fallen into a brown study. The more energetic Brian Westhelm resumed the narrative.

‘We’ve kept the matter quiet so far. Matthew suggested bringing in M. Poirot, in the hope that it could be dealt with discreetly.’

‘Yes; Poirot has had wide experience in matters of this sort,’ I said, removing the envelope of Mrs. Adelaine Brooks from under Carrington’s glazed expression, and frowning at him a little suspiciously. He didn’t seem to notice, though, and continued to look down at Poirot’s bills. Finally he looked up again, as though remembering his purpose in coming.

‘Captain Hastings, would it be possible for you and M. Poirot to come round to our aunt’s house this afternoon? We have not yet told her about her necklace, and I daresay the truth of the matter would come better from the two of you. It will comfort her to speak to someone she knows is on the case.’

* * * * *

When Poirot returned, I met him in the hall. ‘You missed some visitors,’ I said straightaway, as he doffed his hat and coat. ‘Two men. Apparently their aunt, a Lady Westhelm, had missed a piece of jewellery herself, like your Mrs. Brooks, and– ’

Now it was Poirot’s turn to interrupt. “And she found it again some time later, and it was discovered to be a forgery.’ Seeing the stricken expression on my face, he added, ‘I found the brooch of Mrs. Brooks; or rather, I did not find it. I located for her, in her house, a brooch of identical description, set with pearls and rubies. It was paste. The first thing I do, you comprehend, when discovering missing jewels is to check their authenticity. You do remember, mon ami, the case of Mrs. Opalsen’s pearls at the Grand Metropolitan?’ I nodded, bewildered at this development.

‘And also,’ he continued with a twinkle, ‘Mrs. Brooks is acquainted with Lady Westhelm, and they had already commiserated on their missing jewels. I was told about Lady Westhelm’s missing necklace and deduced a second forgery.’ Steering me into the sitting room, Poirot said, ‘Now tell me everything, my dear Hastings, everything about the visitors who came to call– with method, if you please!’

I related the conversation we had shared as thoroughly as I could. Poirot nodded occasionally, then walked over to his desk to sit. Suddenly I heard an exclamation.

‘Sacré! You have been sitting at my desk again, Hastings!’

Shamefacedly, I admitted the fact. Poirot picked up his stack of mail, which I had shuffled untidily, and proceeded to make the stack perfectly neat again alongside the paper knife.

‘Westhelm seemed awfully curious about that letter from Mrs. Brooks of yours,’ I said. ‘And so did Carrington, come to think of it. Spacey sort of chap. Even when I moved the letter, he just kept on staring down at your bills as though they puzzled him.’

‘Is that so?’ murmured Poirot. ‘That is most interesting.’ He picked up the envelope containing Mrs. Brooks’ letter and examined it. Then, he slowly picked up the envelopes with the bills and examined them, one at a time. I could not see the point of this little exercise in the slightest, but when he got to the final bill (from his tailor), I heard a faint ‘Ah!’

Poirot was standing very still, looking at the papers in his hands, his eyes gleaming like a cat’s. ‘I wonder.’

‘What is it?’ I asked, devoured by curiosity.

‘A little idea, mon ami, that is all. C’est curieux.’

‘Do you think that Carrington knew about Mrs. Brooks’ robbery– that he in fact planned it, as well as the theft from his aunt?’ I wondered, though what this had to do with Poirot’s bills I could not begin to guess.

‘As usual, you misapprehend my train of thought, Hastings. And I could not possibly know anything of the sort at this moment. But clearly, these two women’s cases are connected; of that there is no doubt. I believe we shall have to pay a visit to this Lady Westhelm, tout de suite. But first, we replenish the grey cells with le déjeuner.’

He rose from the desk, and we prepared to leave together.

* * * * *

After a bite of lunch, I drove the two of us to Rathene Hall, home of Lady Westhelm. A surly butler opened the door to us, Poirot presented his card with a flourish, and we were shown in. Westhelm and Carrington descended the stairs to meet us. They greeted Poirot with enthusiasm, and led us into a parlour where the lady sat in state.

Lady Westhelm had that quality, possessed by any number of aristocratic women, of appearing both gracious and slightly forbidding, with tightly-bound, greying hair and an imperious expression. Nearby, a young lady’s maid stood, pretty and efficient-looking, arranging a vase of flowers on a nearby table. She started visibly when the four of us appeared, and I followed a penetrating and questioning gaze from her to Mr. Westhelm. I could not make out the expression he returned, but the girl’s hand suddenly stole to her apron pocket, which she touched quickly before resuming her task. Poirot seemed to notice, too, but he glanced away again as though disinterested and approached the older woman.

‘Madame,’ said Poirot to Lady Westhelm with a little bow, ‘I am pleased to make your acquaintance. Earlier today, I have been to see a friend of yours, Mrs. Adelaine Brooks, in my professional capacity.’

Lady Westhelm nodded, unsurprised. ‘Adelaine told me some weeks ago that she was unable to find her brooch. She mentioned several times that she thought of consulting you.’ The lady eyed Poirot skeptically, taking in his dandified and distinctly foreign appearance. ‘But one should not jump to conclusions. Getting outsiders involved in domestic affairs should be a last resort, I feel. I advised her to continue looking for it herself. These things turn up after some time. Why, even I have misplaced some jewels, and rather recently, but they have been found again. Is that why my nephews have bidden you to come see me?’

‘These gentlemen,’ said Poirot, ‘were concerned that the necklace you recovered might be a forgery. The brooch of Mrs. Brooks, which I located in her house today, was itself a cleverly-executed paste copy. If you would be so amiable as to perhaps let me see this necklace, I can confirm how things stand.’

The words certainly had a ruffling effect on Lady Westhelm. She turned to her young maid and said sharply: ‘Fetch the turquoise necklace, Parker.’ The maid cast an alarmed look at all of us, and another fleeting glance at Mr. Westhelm, before hurrying out of the room.

She returned in a moment with a small black jewel case, and at a sign from her mistress, handed it to Poirot. He opened the case and lifted out a gold necklace dripping with turquoise. Retrieving his pince-nez, he proceeded to make a careful examination of the piece, then put it down with a sigh, turning to Westhelm and Carrington.

‘Your fears are confirmed,’ he said, adding to Lady Westhelm: ‘It is true. This piece is a worthless forgery.’

I pass over the extent of the great lady’s subsequent litany of disbelief, acceptance, shrieks, and general commotion, which Poirot pacified somewhat by promising to do all that he could for her. He proposed to question the members of the household in turn to glean any information that each could remember, insisting that the memories could be best recovered by questioning each person individually.

Carrington willingly accompanied Poirot into a little alcove in the hall, while Westhelm and the maid waited in a study opposite. The door was open, and I could see them clearly from our position. Their heads were together and they conversed in low tones that seemed most uncommon for a maid to adopt with a nephew of her mistress. A little bewildered, I turned back to Poirot, who was asking Carrington about the family and household in general; was it a harmonious one?

‘Oh, Auntie’s not a bad sort, once you get used to her,’ said Carrington, with feeling. ‘She’s rather old-fashioned in her ideas about people, of course, but I suppose that’s to be expected. Brian– Mr. Westhelm, that is– and I get on wonderfully with each other, but I’ve gotten the feeling lately that he and Auntie have done a bit of quarrelling. Poor devil’s had some trouble with some investments, and his creditors are starting to come round. I’m not too badly off and have offered some assistance, but he won’t hear of it.’

‘This falling out– was it because he asked Lady Westhelm for assistance?’

‘No, it’s not that,’ Carrington said, hesitating. His eyes flickered into the room across the hall where his cousin stood. Then he crossed his arms, his sad eyes looked into Poirot’s, and he said enigmatically: ‘Auntie can be damned unfair about people sometimes.’

‘I comprehend, Monsieur.’ I wondered what Poirot had comprehended, because the statement communicated very little to me. ‘Now, what can you tell me of the lady’s maid, Mademoiselle Parker? She was in the habit of handling her mistress’s jewels, yes?’

‘Miss Nettie Parker took the job of lady’s maid here about a month and a half ago, I understand. She’s done jobs as companion or maid for several of the matrons in the neighbourhood. I suppose she frequently handled Auntie’s jewellery. But if you’re asking whether she’s likely to be a thief, I’d call that nonsense. A nice girl, perhaps a little simple sometimes. Brian’s here visiting more often than I am, and I know he thinks she’s a brick.’

‘Thank you. If you would have the kindness to wait in the parlour with your aunt while I speak to your cousin, I would be much obliged.’ Poirot bowed, and Carrington departed. My friend turned to me. ‘Retrieve M. Westhelm for me, please, Hastings.’

I ducked out of the alcove and made for the open study door, but what I saw brought me to an abrupt halt. It happened so quickly, but the gesture was unmistakable. It was Miss Parker, one moment with an opened envelope in her hand, whipped from her apron pocket… the next moment, she had thrown it into the fire in the grate.

I turned back to Poirot, aghast. ‘Did you see that?’ I whispered.

His eyes narrowed. ‘Oui, mon ami,’ he replied, ‘and so did Westhelm. Yes, I should like to speak with him next.’

When Westhelm had been brought to our alcove, leaving Miss Parker alone in the study, Poirot dropped his voice to address him. ‘Monsieur, I want you to think very carefully before you answer my question. The necklace of Lady Westhelm, when she thought it to have been found. You saw it a few days ago, and you were of the opinion that something was wrong. Recall– what about that necklace did not look quite right to you?’

Westhelm appeared to be concentrating deeply. ‘I’m sure I couldn’t say. I’d no idea at the time, only the impression that something was wrong. But–’ he said suddenly, with a snap of his fingers, ‘I think it might have been the stones themselves. Yes, it was. The pattern on them looked quite different.’

‘I see,’ said Poirot. He looked satisfied, but grave. ‘It would be in your best interests to keep that information to yourself for the present, Monsieur. I, Poirot, advise this most firmly. And perhaps, you would also now be good enough to tell me what your relationship is with the lady’s maid, Mademoiselle Parker.’

Westhelm froze. Clearly he was not expecting the question.

‘I see you are not interested in answering. Eh bien, perhaps I can try a different tack: what was in the envelope Miss Parker burned in the grate just now, in the study?’

‘That,’ the young man said stiffly, ‘is none of your business. You’ve been asked here to investigate this business with my aunt’s necklace, not pry into other matters.’

‘Pardon, I am most maladroit. I ask you, then, what I asked your cousin: your family in this place, they are harmonious? And your aunt, you get along?’

Westhelm’s underlying frustration was more evident than ever. ‘I have been quite harmonious with all my relations… but Auntie… she can be unreasonable sometimes.’

‘Thank you, Monsieur,’ Poirot repeated with a bow, and again requested that he join his aunt and cousin in the parlour while he concluded his interviews with Miss Parker. Westhelm left, looking discomfited, and Poirot surprised me by asking me to join them as well.

‘I shall not be long with Mademoiselle,’ he said firmly. I took my leave reluctantly, wholly baffled by Poirot’s abrupt lines of inquiry. From my point of view, we did not seem to have gained any useful information at all!

* * * * *

When we bade farewell to the household of Lady Westhelm shortly thereafter, Poirot announced that he had some further investigations to conduct that would take him a full week. He did not want to trouble Lady Westhelm, but would the two cousins and Miss Parker please call on us at Whitehaven Mansions one week from today, at which point he was sure to have more information to share? They agreed: Westhelm a little sullenly; Carrington, with visible relief; and Miss Parker, with bemused hesitation.

I was eager to see how Poirot meant to proceed with his investigations in the following week; figure to yourself my intense annoyance when he seemed to do absolutely nothing at all! He did not even deign to discuss the case with me. ‘But I have done my work, mon ami,’ he insisted as he sat at his desk, trimming his moustache complacently. ‘I placed a call to the Chief Inspector Japp. He will be of great assistance.’

I was incensed at the notion of Poirot just handing this over to Scotland Yard without further legwork– two different jewel robbery cases, no less– but I learned long ago that doing battle with Poirot at his most inscrutable was a losing game.

Our visitors arrived together the following week, and Poirot greeted them graciously. He steered everyone straight into the kitchen, where he had prepared sandwiches and tea.

‘Permit me, Hastings,’ he said quietly, and he opened again the front door I had just shut, leaving it slightly ajar. A single look from him enjoined me to leave it so and say nothing. I obeyed, mystified.

We all settled down to our refreshment. Poirot regretfully informed our guests that there had not been many developments yet, but shared some thoughts and speculations about elderly ladies as victims of jewel robberies in the abstract, relating a few of his past cases. Suddenly, Poirot gave a sharp cry and reached toward his mouth.

‘Mon Dieu, it is the toothache! It has troubled me for some days, has it not, Hastings?’ This was a clear sham; the first I’d heard of a toothache. I managed to return a sympathetic expression. ‘A little brandy would be of great relief,’ he added. Carrington hopped up to fetch the brandy from the sitting room, and Poirot received it with many thanks.

At length, Westhelm said, ‘Well, I suppose we must be going.’ The party rose from the table and prepared to depart.

‘Bien sûr, my friend, although, perhaps first…’ he paused. Our three visitors looked up. Poirot beckoned us into the sitting room, and as we entered, he strode over to his desk, standing behind it and facing us. He bent down to make some observation, then gave a sharp nod and looked up at us again.

‘And now perhaps, M. Carrington,’ he said pleasantly, ‘you will be so good as to replace that which you removed from my desk just now.’