I haven’t done an episode review for awhile now, so here’s one I’ve been mulling over in the last few days. 🙂

Things I Loved:

–Making Poirot’s friend Bonnington his dentist also. Doing this scores a couple of script writing points. First, it provides some insight to Poirot’s character which is reiterated elsewhere in the series (he hates going to the dentist). Second, Poirot’s aching bicuspid makes a convenient excuse for him to meet with Bonnington a second time, so he can hear the news of Henry Gascoigne’s death; in Christie’s original, they meet again randomly on the Tube. Finally and most importantly, it makes the references to the dead man’s teeth seem natural and consistent with the rest of the story, and serves to slightly conceal the vital clue.

–The contrast of the opening scene. Brighton’s frivolous outdoor revelry is sharply contrasted by the interior shot of the dying Anthony Gascoigne.

–A tiny detail in the closing scene, but I thought it was great anyway– when the lads are gathered again at the restaurant at the end, you see Molly come through the shot from the back left, bearing two plates of a dessert that might conceivably be the blackberry crumble and depositing them before customers. This is an exact parallel of one of the last lines of Christie’s story, and I appreciated the touch.

–Mrs Mullen, the neighbor of Henry Gascoigne, treating Poirot like he’s deaf or unable to speak English– SO funny.

-Bringing food into the rest of the story. Many of the early scripts, especially those based on the “slighter” short stories, take elements from Christie’s original and incorporate the themes into the other characters’ storylines. (For example, in The Cornish Mystery, Mrs Pengelley’s digestive troubles and diagnosed “gastritis” parallel Hastings’ stomach issues and diet.) The crux of Four and Twenty Blackbirds is one man’s eating habits which give away a crime. The script writer for this episode adds the delightful scene of Poirot cooking for Hastings, which is also a good excuse to throw in some Belgian references. The line, “Please– do not be stinting with your praise” is one of my all-time favorite moments of Poirot vanity. 🙂

–Miss Lemon’s wireless program. She is listening to a radio drama featuring A.J. Raffles, “London’s Man of Mystery.” He and his sidekick Bunny were modeled from Holmes and Watson; she describes Raffles as “such a dashing figure.” You could read this as an early indication that Miss Lemon finds the whole renowned-London-detective-character attractive, and it elicits a very interesting look on Poirot’s face when he hears it. Of course, in the books, Miss Lemon wouldn’t touch detective fiction with a ten-foot pole (see: Dead Man’s Folly), but the discrepancy doesn’t trouble me. Oh, and the fictional Raffles is also a CRICKETER! Considering Hastings’ cricket mania in this episode, is this a coincidence?

-The forensics team at Scotland Yard, which would go on to send Poirot a get-well message after his bout of food poisoning in Evil Under the Sun. 😀 And Japp absolutely cracks me up in the scene at the Yard in which Poirot is trying to wheedle some information out of him. His “scrap heap of scrap” and his “I didn’t”… ha! And in the midst of the humor, and despite his skepticism of Poirot’s interest, you nonetheless get a good sense of Japp’s own intelligence here.

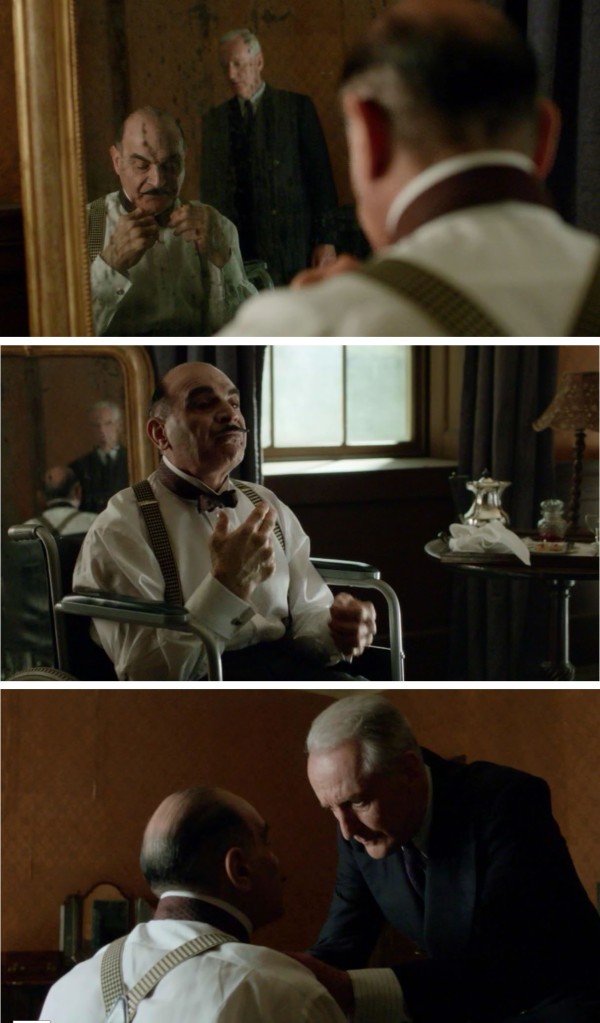

-Speaking of which, I need to hold forth about the denouement of this episode. This is the very first of Poirot’s many dramatic, public reveals. He (rather outrageously) brings the whole Scotland Yard forensic department onto Lorrimer’s stage. When Lorrimer tries to make a dash for it, he is blinded by stage lighting and cops appear to cover all exits. It is done in truly over-the-top theatrical style– practically music-hall, indeed– and foreshadows future denouements with a calculated theatrical setting (Problem at Sea, Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan, Lord Edgware Dies, Three Act Tragedy, The Big Four). But what stood out to me in this early “big reveal” was a reminder of one of the reasons that David Suchet manages the character of Hercule Poirot so well. It’s one thing to say that he’s a great actor and does his homework and all that– true, but the same can be said for Ustinov and Branagh, and I don’t really want their Poirots. There is a combination of characteristics that Suchet seems to have a natural facility for playing really, really well. The “foreigner” is an obvious one. But in dramatic reveals like this one, a duality in Poirot’s personality is displayed in striking fashion: on the one hand, an extremely charming and/or charismatic gentleman; on the other, a figure who is ruthless to the point of death, and deadly terrifying as a result. Several of Suchet’s very best roles of screen and stage have featured this duality of character, including Robert Maxwell, Rudi Waltz, Melmotte, and Iago. Christie wrote this contrast into her own character, and to see someone of Suchet’s experience and skill have at it is absolutely inspirational.

Things I Didn’t Love:

-Hastings himself was a bit weirded out by the vaguely voyeuristic overtones of the awkward moment in the gallery when Dulcie Lang is posing for a life class. I mean, points for character representation of Hastings, I guess. Not devastating or anything as a moment, but awkward.

-For all the fun of the denouement, there were some curious choices in the general unraveling of the crime. The biggest clue in the story were the “blackbirds”– or blackberries– that the dead man with the unstained teeth was supposed to have eaten. This discovery of Poirot’s was revealed not at the climax of the story, but in the middle. Likewise, the supposition that the last meal that Gascoigne had eaten was not dinner, but lunch, became a deduction made along the way. The dramatic denouement was really more about informing Lorrimer how much tangible evidence they had against him. Part of me wanted a bit more recap at the very end as to just why Lorrimer’s performance was “fatally flawed” (mainly, because he forgot to eat like his uncle).

Things That Confused Me:

-If you were already familiar with the story, the dynamic shifts in the TV plot may cause a little confusion generally. In the book, Anthony Gascoigne had married a rich wife and was consequently well off, while brother Henry was an “extremely bad” artist who was poor. Lorrimer had to wait until Anthony died, because the money would come to his brother, who he had to kill shortly afterward, hence the careful timing of the murder. In the episode, Anthony may or may not have been well off, but Henry was, including assets that could only be sold after his death. If Henry Gascoigne is the rich one, why does Lorrimer have to wait until after Anthony dies to kill Henry? Instead of the chain of inheritance, the focus is shifted so that the very existence of Anthony serves to provide other plot elements: another suspect for the impersonator, some background as to the brothers’ quarrel and the influence of an artist’s model, and just general red herring-ness. It seems the story almost could have been told without Anthony.

-It was something that puzzled me in the book as well– how does George Lorrimer know that Anthony Gascoigne had made no will (or in the book, no recent will at least)? Since the twin brothers had a very long-standing quarrel, it makes sense that they’d consider cutting each other out of their wills if they’d had any.

-Why does Mrs Mullen, the observant neighbor, unlock the door of Gascoigne’s house and let Poirot and Hastings in, since she’s so suspicious of them? And if she knew that Dulcie Lang was upstairs, why “break in” at all– why not just ring?

-In Poirot’s first meeting with Dulcie Lang, he surreptitiously cuts a small piece of blotting paper from the blotter on Henry Gascoigne’s desk. We don’t discover what this is all about until the stage scene, where he reveals how the deception with the smudged postmark was done. But surely there is no way Poirot could have guessed at that point that the tiny blotter smudges he first saw on Gascoigne’s desk were of any relevance to his death.

-Are we supposed to believe that Dulcie Lang’s passionate retort that she would never part with Gascoigne’s paintings at any price indicates some romantic interest? It kind of comes across that way– and the deceased was not young, just saying.

-The restaurant in the book was called the Gallant Endeavor. This was changed to the Bishop’s Chophouse in the episode, and was accordingly filmed at the oldest chophouse in England, Simpson’s Tavern. This is all well and good, since the Gallant Endeavor is supposed to be extremely British in its cuisine, shunning all things hinting of the continental, and has all the marks of a chophouse. However, I don’t really understand why the sign “Simpson’s” is clearly visible on the outside of the restaurant as it was filmed, as characters in the episode clearly refer to it as the Bishop’s Chophouse.

************

Conclusion: What can I say? I do love it! In all of its inimitable, sweater-vested glory! 🙂